FIlterTube:Investigating echo chambers, filter bubbles and polarization on YouTube

Beside this textual report, you can enjoy the presentation. — Students and researchers worked on this research for four days in January 2021.

Participants: Bruno Sotic, Nilton Da Rosa, Paul Grua, Armand Bazin, Maxime Bertaux, Youcef Taiati, Antonella Autuori, Andrea Elena Febres Medina, Wen Li, Inga Luchs, Annelien Smets, Lynge Asbjørn Møller, Alexandra Elliott, Matthieu Comoy, Ali El Amrani, Eirini Nikopoulou, Nicolas Pogeant, Yamina Boubekeur, Arthur Lezer, Mehdi Bessalah, Andrea Angulo Granda, Tcheutga Corine, Lisa Lan, Kaothar Zehar, Dong Pha Pham, Josue Charles, June Camille Ménard, Minhee Kyoung, Hangchen Liu, Yiran Zhao.

Group facilitators: Salvatore Romano, Davide Beraldo, Giovanni Rossetti, Leonardo Sanna.

Abstract

This paper studies the construction of filter bubbles and political polarization under YouTube ’s algorithmic personalization, in a time where the political division runs deep in the US and the 2020 election reaffirms the polarization. Using artificially generated personalized user accounts, we find that search results differ according to users’ political affiliations, both in terms of the media type and political ideology of the channels suggested, showing some empirical evidence of filter bubbles’ existence on YouTube, which possibly exacerbates an echo chamber behavior and enhancing political polarization in the US political debate.

Introduction

The consumption of news on online platforms is increasing year after year. While the video-sharing platform YouTube has become known as the place where users can find almost anything, it is also becoming an essential news source. About a quarter of all U.S. adults (26%) consume news from YouTube, and about 78% of them in some way or another rely on the YouTube algorithm’s recommended news videos (Pew Research Center, September 2020). Thus, algorithmic mediation is a crucial issue for our democracy. This project investigates the emergence of filter bubbles, echo chambers, and polarization within YouTube ’s recommender system with the U.S. post-electoral debate as a case study.

In the run-up to the 2020 U.S. elections, YouTube announced specific measures to curb the spread of fraud or errors that could influence the election’s outcome and made efforts to connect people with authoritative information. Therefore, the U.S. post-electoral debate moment provides insight into the valid test on the intimacy between YouTube ’s personalization algorithm and the possibility of polarization.

The project distinguishes between echo chambers and filter bubbles. Echo chambers describe loosely connected clusters of users with similar interests or political ideologies, formed by its members discovering and sharing only information within set interest or ideology (Zimmer et al., 2019). The users themselves thus create echo chambers. Filter bubbles, on the other hand, are a direct effect of algorithmic personalization. The filter bubble argument has dominated the narrative on personalization since the publication of Eli Pariser’s influential book on the subject (2011) arguing that algorithmic personalisation only provides the user with more of the same, thus reducing the diversity of information and opinions that people are exposed to and subsequently increasing polarization. Polarization refers to the process of increased segregation into distinct social groups, separated along racial, economic, political, religious, or other lines (Castree et al., 2013). However, how the YouTube algorithm amplifies extremist voices and isolates users into “filter bubbles” pushes them into a polarized situation concerning in such a crucial period (Nikas, 2018).

Current empirical evidence supports a more nuanced view on filter bubbles, and many scholars have criticized the concept and cast doubt on the fear of filter bubbles (Bruns, 2019; Zuiderveen Borgesius et al., 2016). Some studies, however, indicate that YouTube might be an exception. Kaiser and Rauchfleisch (2020) found that YouTube ’s algorithms foster highly homophilous communities, while O’Callaghan et al. (2013) found that the algorithms form specifically far-right ideological video bubbles. Yet, more evidence is needed. In general, the issue is difficult to approach because it entails studying many different user experiences, involving various variables challenging to handle and because it is difficult to produce evidence about the algorithmic personalization using the official APIs. Youtube’s API only allows researchers to access limited amounts of data and does not provide any information about personalized suggestions, hindering studies of the recommender system itself.

This project aims to create a mixed methodology to investigate echo chambers, filter bubbles, and polarization all at once, highlighting the relation between those phenomena. Our approach involves artificially creating echo chambers on YouTube by controlling a group of users’ watching behavior, thus personalizing the users. Using the Youtube Tracking Exposed Tool (YTTREX), we then assess whether the algorithm behind YouTube ’s recommender system personalizes these users’ search results and recommended videos to an extent where we can talk about the creation of a filter bubble. Finally, we approach the issue of polarization by analyzing the comments of the recommended videos.

Research Questions

- Does YouTube ’s algorithm enforce a filter bubble and polarization pattern based on an (artificially generated) echo chamber?

- Sub-RQ1: Are there differences in the videos suggested as search results across different user types?

- Sub-RQ2: Are there differences in comments to the videos suggested as search results across different user types?

Methodology

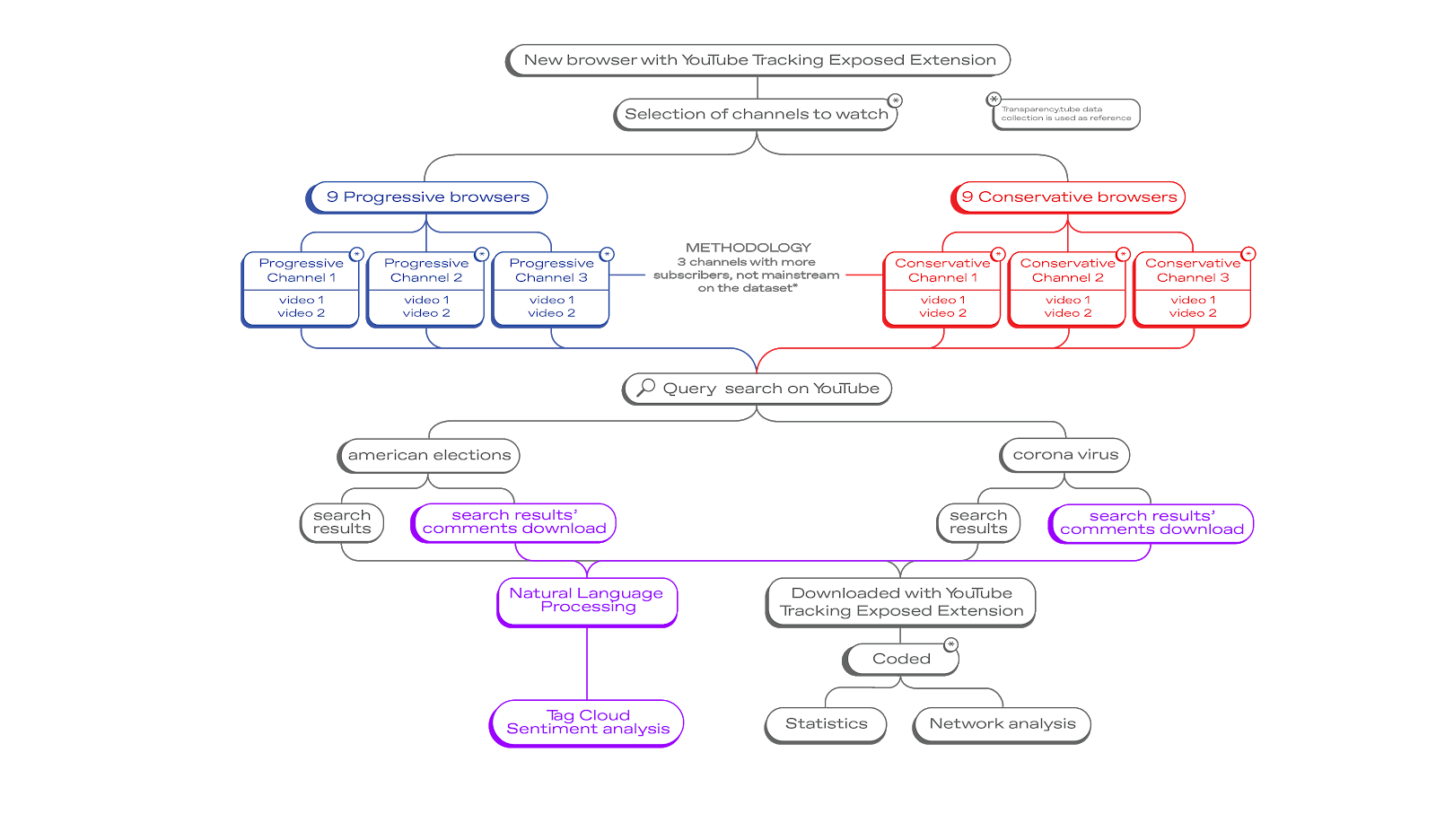

The data collection was divided into two distinct phases. In the first phase –the personalization phase– we aimed to simulate echo chambers on YouTube with our watching behavior. To this end, all participants of the project were divided into two groups, each group representing a political orientation in US politics (Conservative/Republican and Progressive/Democrat).The categories of “progressive” or “conservative” of videos and channels were retrieved from the transparency.tube project. Using a clean browser, each user watched six videos from channels considered either progressive or conservative depending on the assigned group, thus personalizing the content that the user gets recommended on the platform. In the second phase – the data collection phase – all users performed three YouTube search queries; “American Elections,” “Coronavirus” and the control query “New Year.” The search results were scraped by the YouTube Tracking Exposed (YTTREX) browser extension, a tool that scrapes metadata from YouTube, such as recommended videos or search results. The tool enables collaborative research. It assembles data collected by all browsers with the extension installed, allowing for comparison by letting the user download a CSV file with all relevant information (Sanna et al., forthcoming).

The data was cleaned and manually coded to allow for thorough analysis. Due to some users’ technical issues, the final data set ended up including approximately nine conservative and nine progressive users. The recommended channels were coded according to media type (mainstream/youtube-native/missing link) and political orientation (left/center/right). Different modes of analysis were then conducted on the data: data flow visualizations, statistical analysis, network analysis, and natural language processing (NLP).

To identify possible patterns in personalized information retrieval, we looked into the data flows between specific media channels present on YouTube and the two groups of users. We mapped those associations through data flow visualizations, quantitative and qualitative statistical analyses. We used the free, web-based software RawGraphs in order to visualise the data flows and the proprietary software Tableau in order to produce the charts.

A small-scale statistical, qualitative analysis was carried out to identify what type of content is offered to particular users in video content retrieval (Buckland and Grey, 1994) to infer the extent to which processes of a feedback loop (Adomavicius and Tuzhilin, 2005) can be thought to be emerging or in progress during the particular research. Also, to infer possible implications of such personalized content retrieval processes for a potential polarisation and / or radicalization of individual users within groups.

To visualize clusters of recommended videos according to user type, network diagrams were constructed using the open-source network analysis software Gephi. On all the network graphs, we used Gephi’s Force Atlas 2 algorithm that provides a layout structure for the arrangement of nodes, situating nodes in proximity to other nodes to which they are connected using measures of gravity and repulsion (Bastian et al., 2009).

We used a Python script to retrieve the comment threads (comments and their replies if existing) for each of the videos recommended as a result of our queries. Our intent was to be as close as possible to exhaustivity allowed by the Google API. We found that getting the top 100 threads by relevance, as defined by the YouTube platform, was sufficient. This yielded approximately 400 000 comments for each query result, which were split between videos suggested to the “progressive” browsers and “conservative” browsers. In order to highlight the difference between them, we excluded comments from videos recommended to both sides. For the “American election” query, this amounted to approximately 65 000 comments for the “progressive” suggestions and 130 000 for the “conservative” suggestions.

The unequal number of comments is due to variance in our original experiment. Conservative browsers scrolled further on the query result pages and thus collected more recommendations. The same was found for the “Coronavirus” query, which led us to collect 75 000 comments from the “progressive” suggestions and 150 000 for the “conservative” ones.

Our first analysis consisted of a simple “bag-of-words” approach, computing statistics such as term frequency normalized as a percentage of each text body. We did not correct the size discrepancy between samples during this step, which is to say the conservative benefited from a more precise analysis (larger sample).

Before analysis, comments were submitted to a cleaning process. The text was reduced to lowercase. Sentences and words were tokenized, that is, broken down into the smallest meaningful units or n-grams (the bigram “Donald Trump” would be kept as one token). This allowed us to remove stop-words (e.g. “and,” “as”…) and separate actual text from punctuation signs, emojis, URLS… that might be irrelevant to some analysis like bag-of-words, but relevant to sentiment analysis.

When deemed relevant, we further reduced the terms into their roots, as expressed by the stem or morphological root word (lemma). This was done using specific stemmers or lemmatizers such as spacy or nltk, trained in the English language, or the built-in tools of Python libraries like Vader.

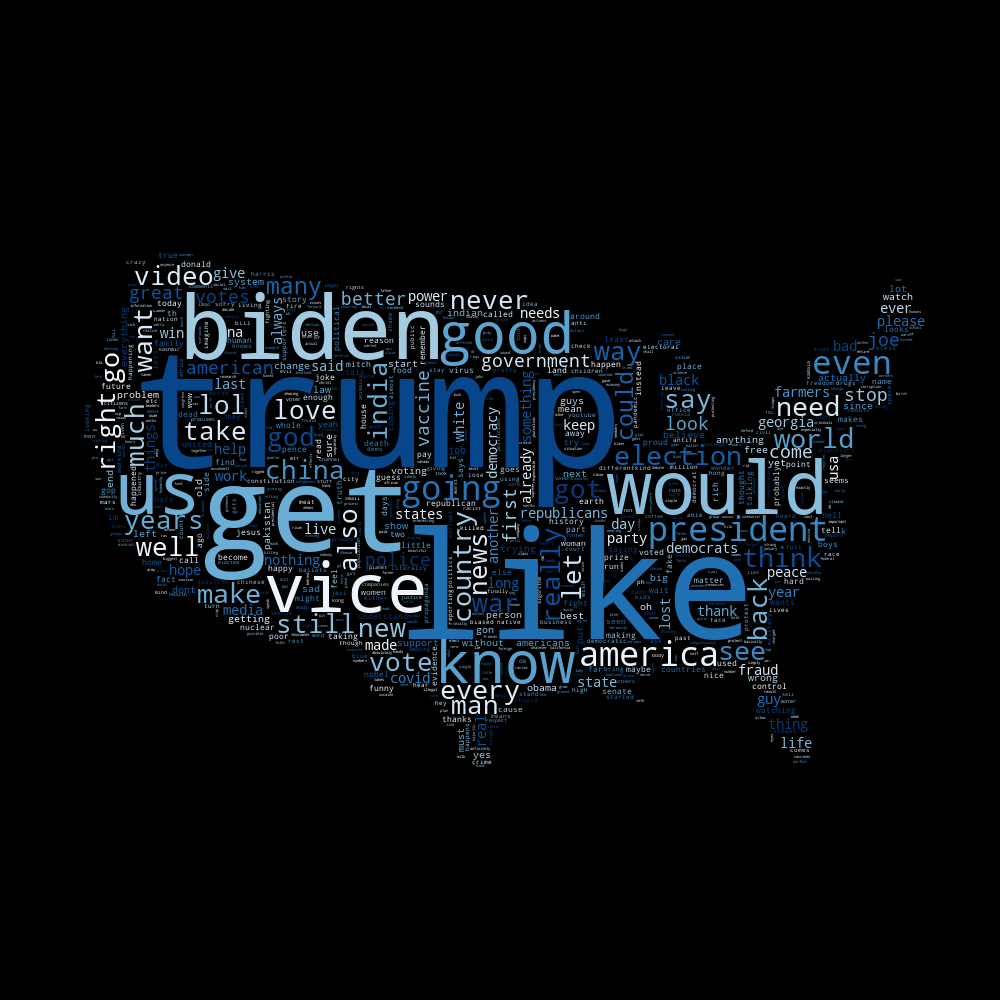

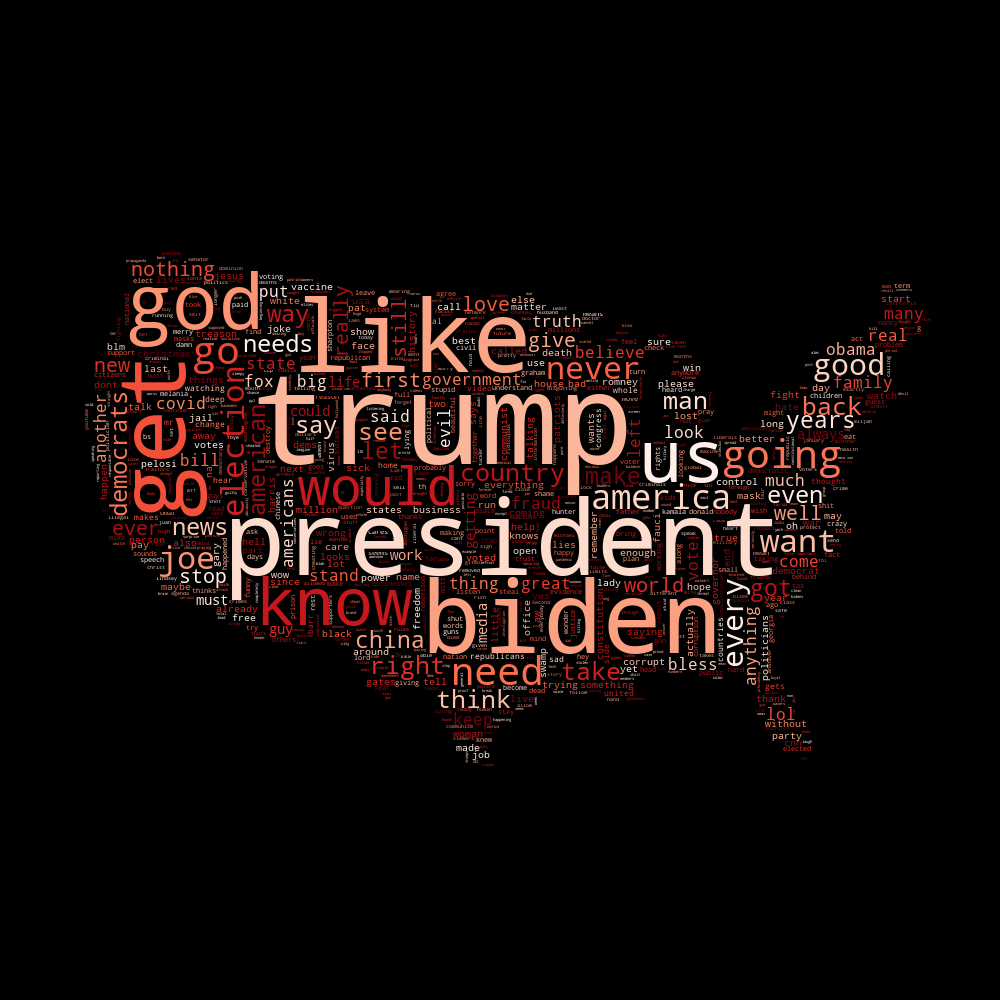

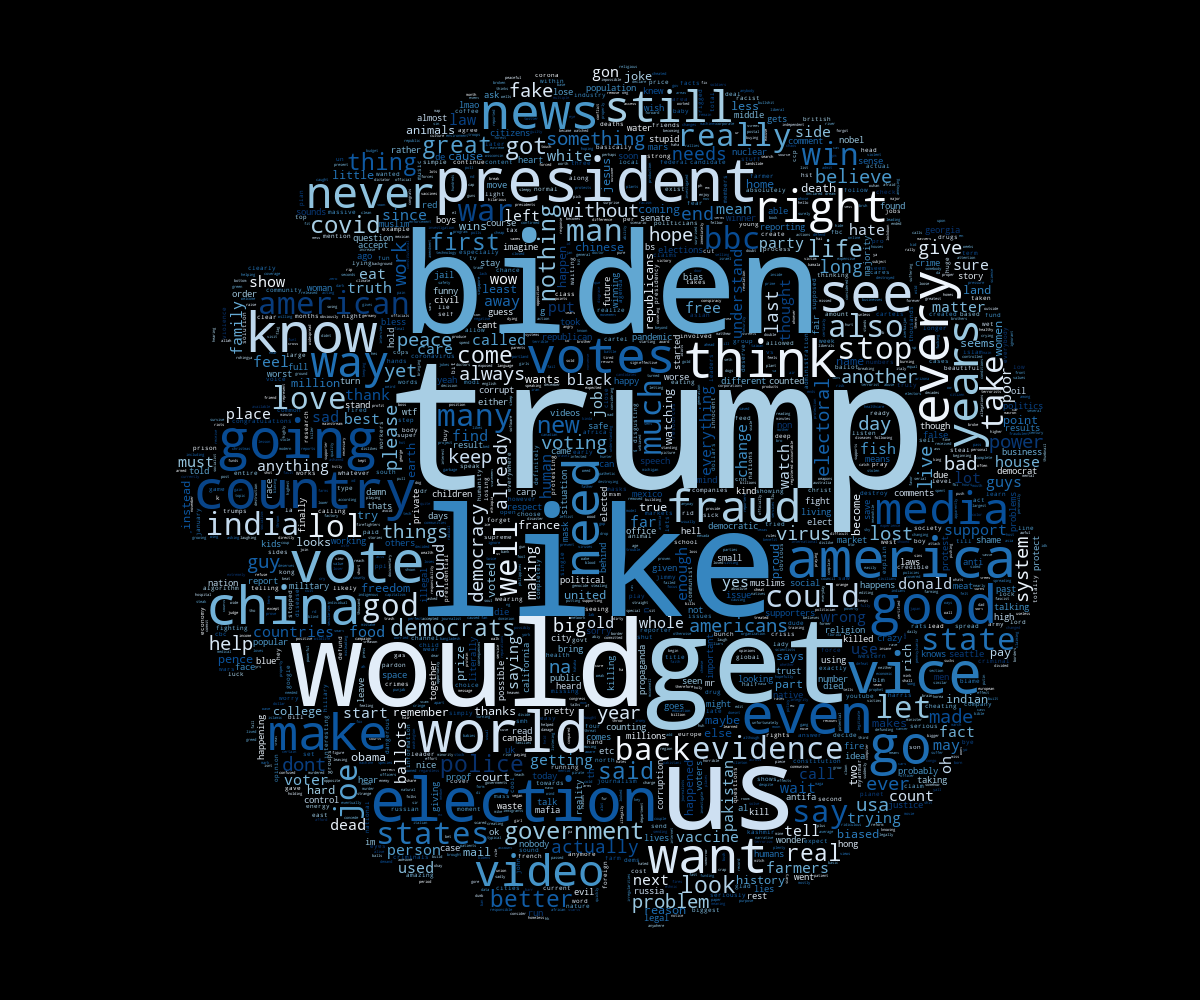

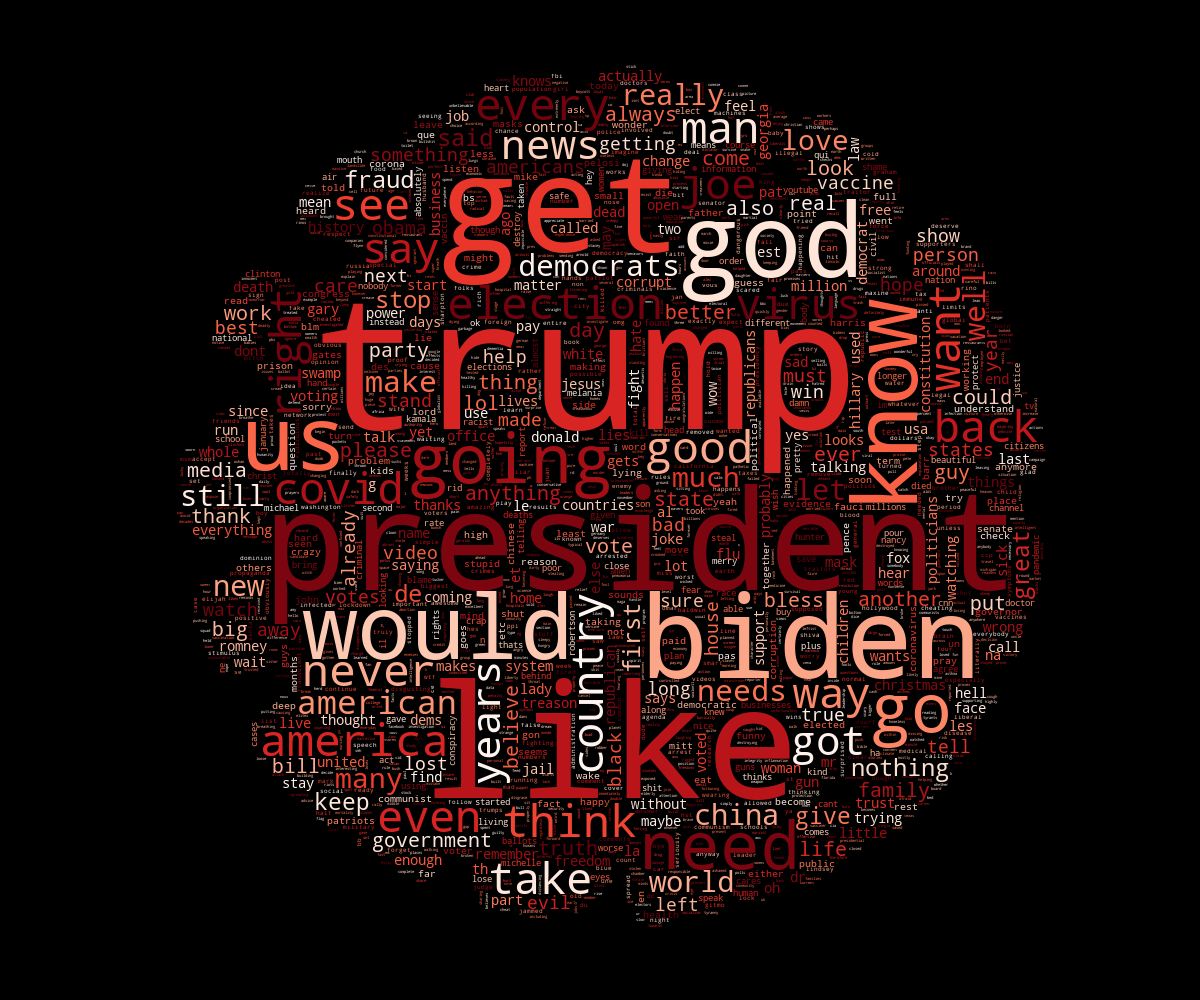

We produced word clouds to illustrate the most common terms for each side and each query. Terms that occur in more than 95% of the comments (e.g., “people” for the American Election query) were removed because they don’t amount to significant insight.

We performed sentiment analysis using the open-source python library Vader, which allows us to gauge the positive, negative, and neutral ratio of comments.

As for the Word clouds that we performed, using all the methods previously explained. Performing the query “american election” we found that the most dominant words s-dominance established by the size of the word in the cloud- for Progressives browser were: Trump, like and Biden, and for the Conservatives: President ,Trump, like, Biden and God.

Query: ‘american election’. Comments’ WordCloud of the videos suggested to progressives users in blue. Comments’ WordCloud of the videos suggested to progressives users in red.

We have noticed that Conservatives’ cloud fit perfectly the Conservatives narrative elaborated around religious value and Republicanism and the Progressives one reflects more a speech on unity and inclusivity which are again, the core content of their narrative.

As for the CoronaVirus queries, we can say that the narratives on both sides are somehow either polluted by the election queries or the election subject has been deeply entangled with it because the dominant words are mostly the same, at the exception of few minor words.

Query: ‘coronavirus’. Comments’ WordCloud of the videos suggested to progressives users in blue. Comments’ WordCloud of the videos suggested to progressives users in red.

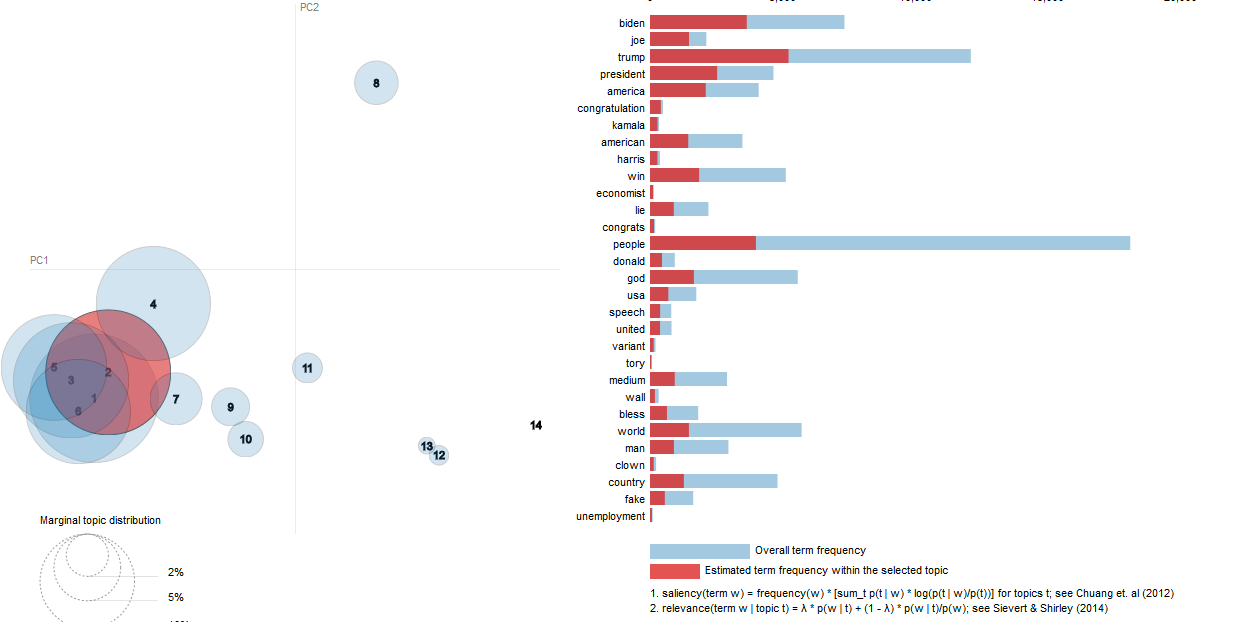

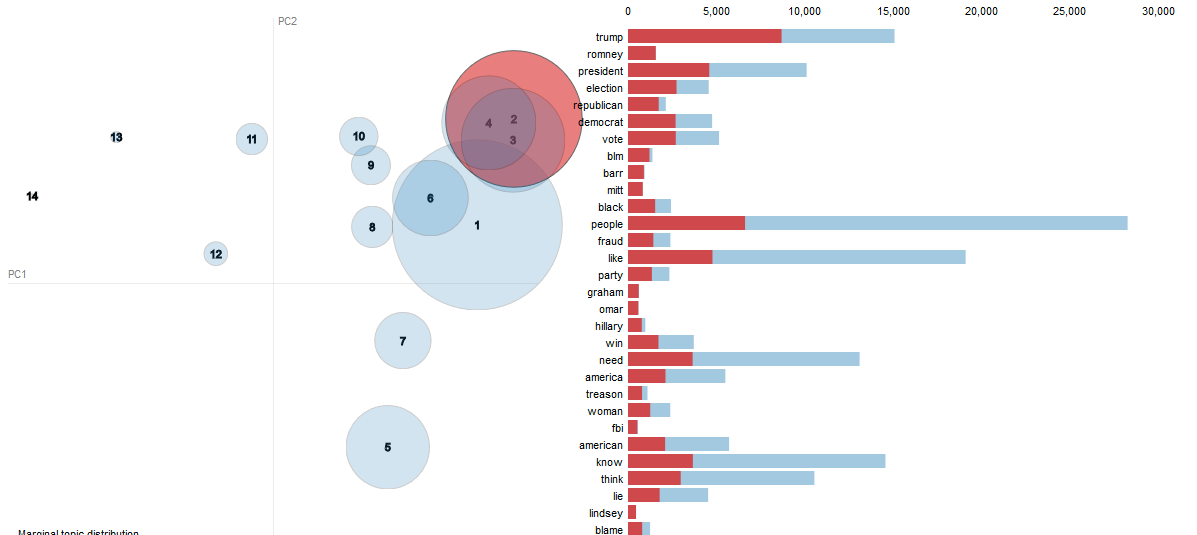

We aimed to compare the topics that were discussed in the comments of each selection of videos. We modeled these topics using Latent Dirichlet Allocation (Blei et al., 2001). This generative algorithm finds k collections of words (topics) that would best recreate the original document if they were “mixed” in proportions according to a specific probability distribution. This being an unsupervised technique, we ran it several times with different values of k and computed a Topic Coherence measure (Röder et al.) to choose the optimal number of topics. We used the open-source library pyLDAvis to visualize these topics. After lemmatization, conservative and progressive corpora were reduced to a similar size. We modeled the topics twice for each query: we first looked at the comments from side-specific suggestions only, then included comments from videos that were offered to both sides.

We computed the Toxicity Index and the Automated Integrative Complexity - AutoIC (Houck, 2014) (Conway, 2014) of the comments across all queries using a metric defined by Gallacher & Heerdink (2019) and coded in an open-source Python library. Words associated with insults or profanity inside the comments are extremely likely to be classified as toxic. This was done on same-size random samples from the comment section of all exclusively ‘‘conservative’ or ‘‘progressive” suggestions of videos for each one of the queries.

Findings

1. Network Analysis and Statistical Analysis Results: Personalization/Polarization of Search Results .

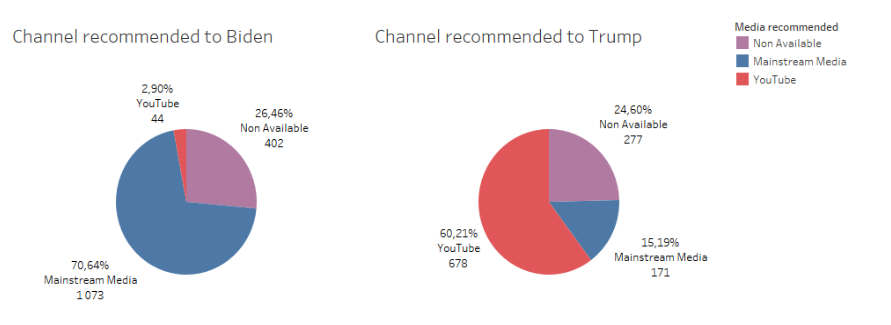

Finding 1: The results for the search “american elections” according to media type indicate polarization, as progressive users are recommended mostly mainstream media, while conservative users are recommended a lot of YouTube -native news media.

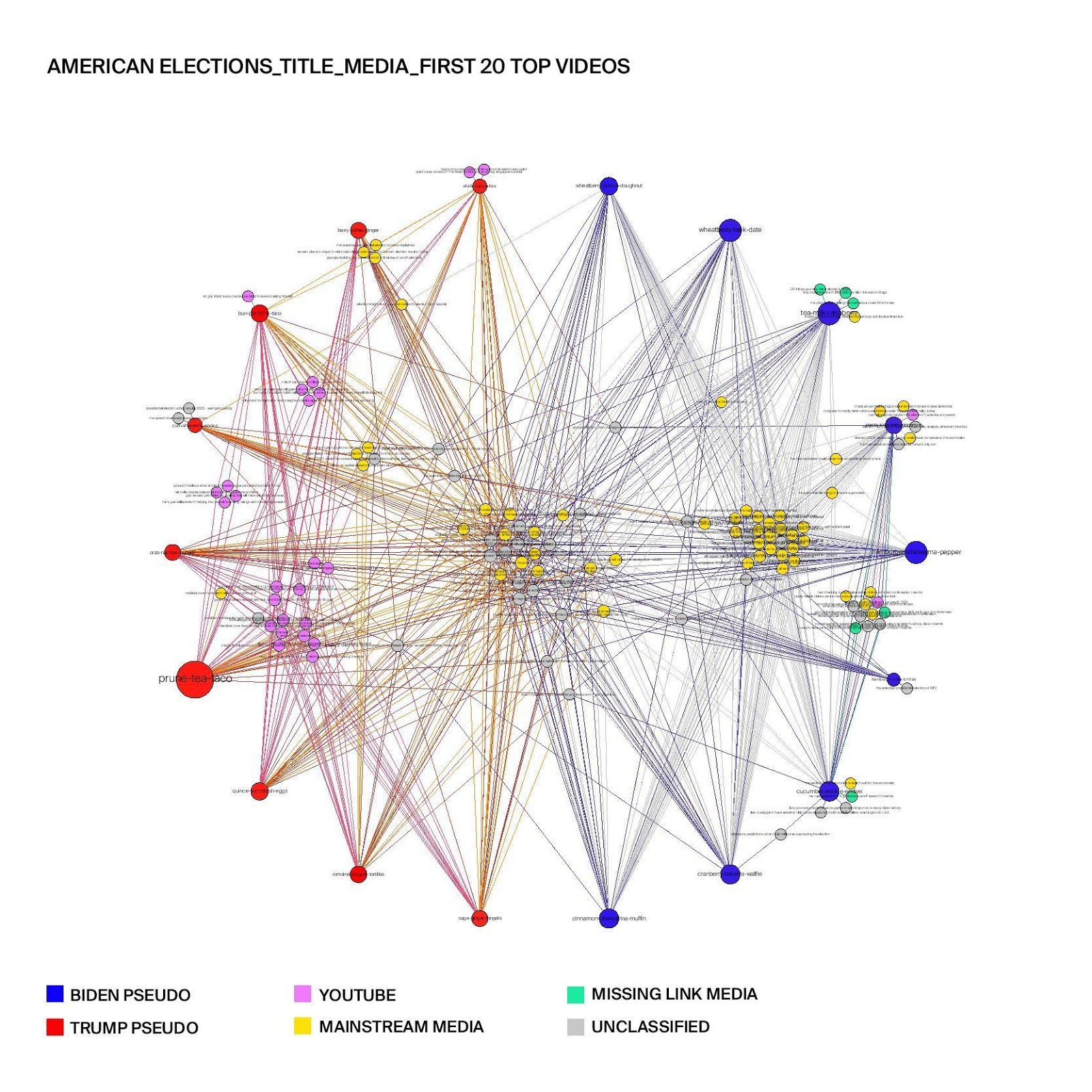

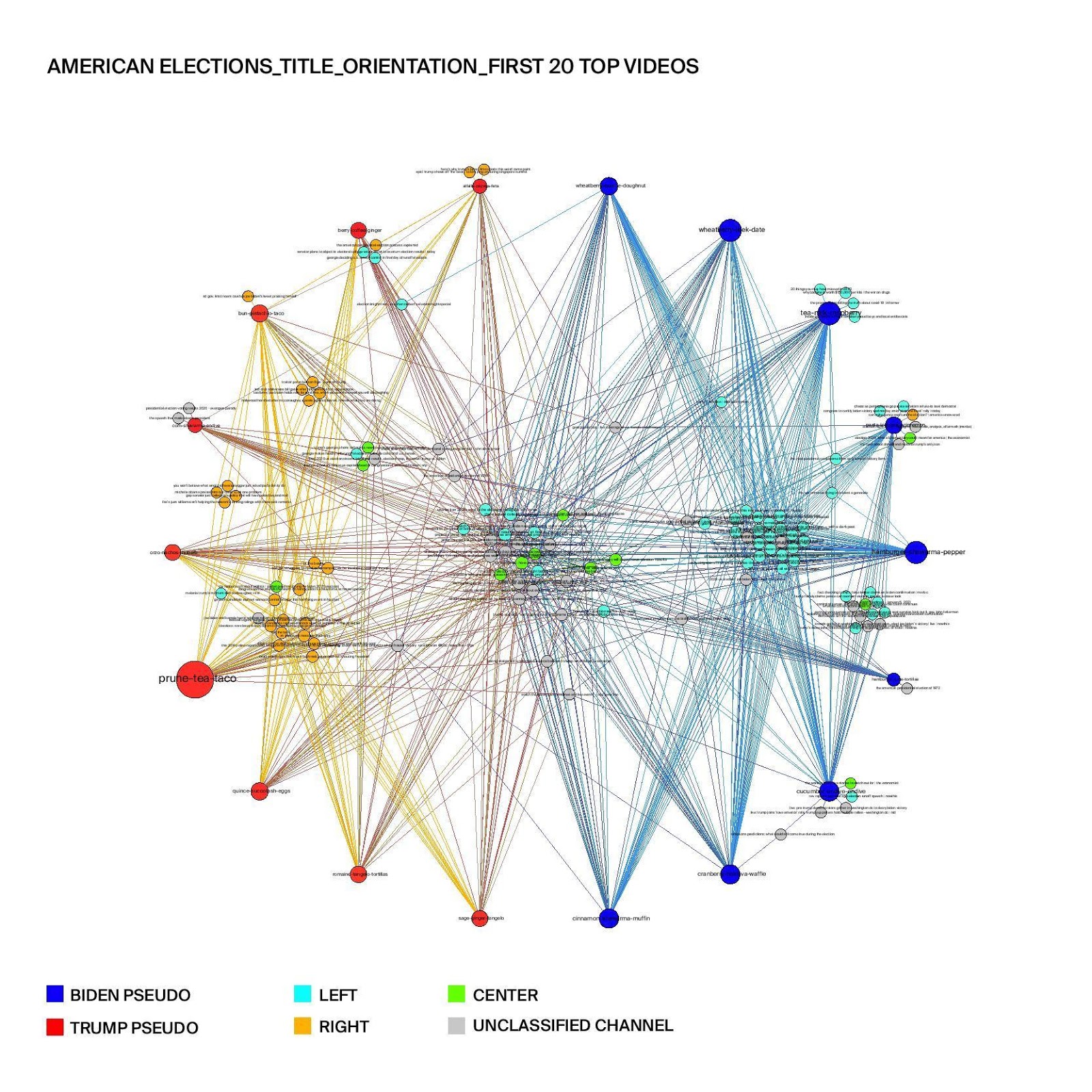

Figure 1: Top 20 search results of “american elections” across conservative (Trump pseudo) and progressive (Biden pseudo) user groups in terms of media types.

Figure 1 illustrates clusters of recommended videos in the search results for “american elections” in terms of media types. It shows that a large cluster of mainstream media videos in the center of the graph, meaning that videos from mainstream media are suggested to most users. However, we can also see some clusters of videos recommended to the specific user groups. Indeed, progressive users are recommended mostly videos from mainstream media channels, while conservative users are recommended a lot of YouTube -native media channels. Nevertheless, most of YouTube -native videos come from the same channels that the conservative users watched in the personalization process, which means that YouTube is simply recommending conservative users more of the same channels that they have already watched. Overall, the results show personalized results for both progressive and conservative user groups.

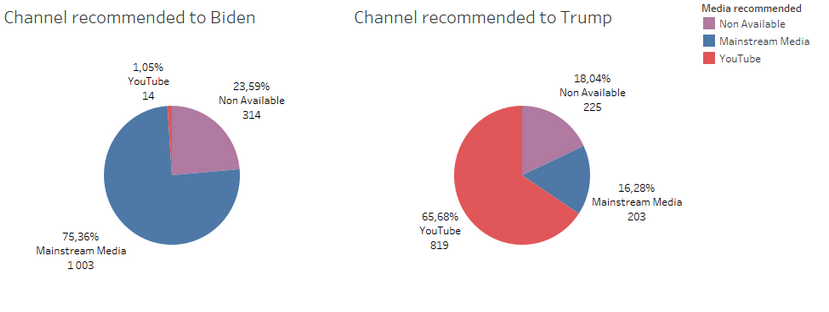

This result is replicated in the quantitative statistical analysis of all the results (figure 2) appearing following the particular query.

Figure 2. Statistical Analysis. Proportion of media type per category of users for the “american elections” query.

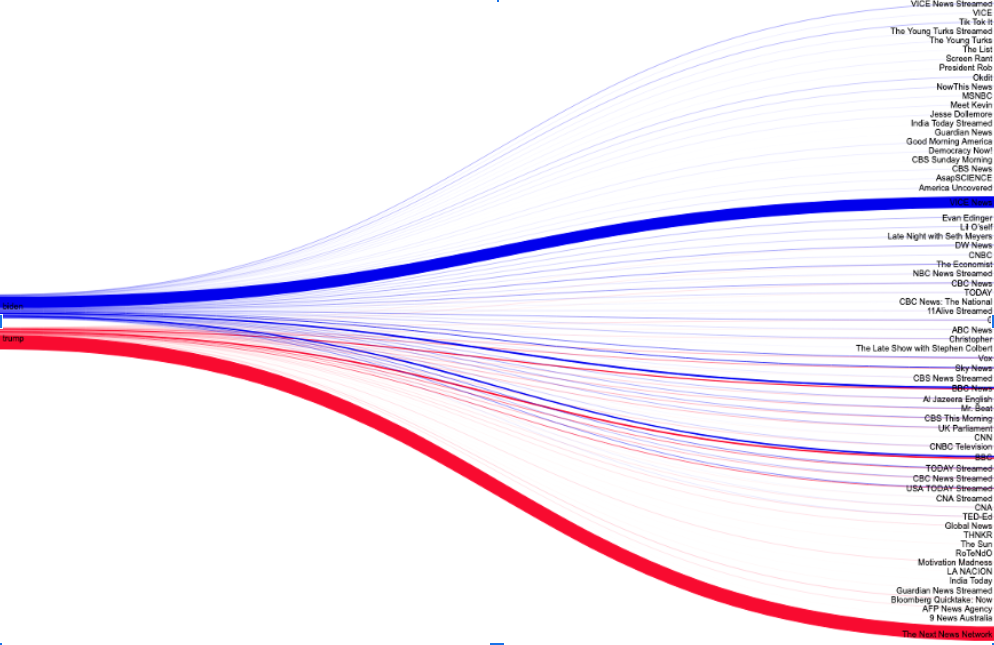

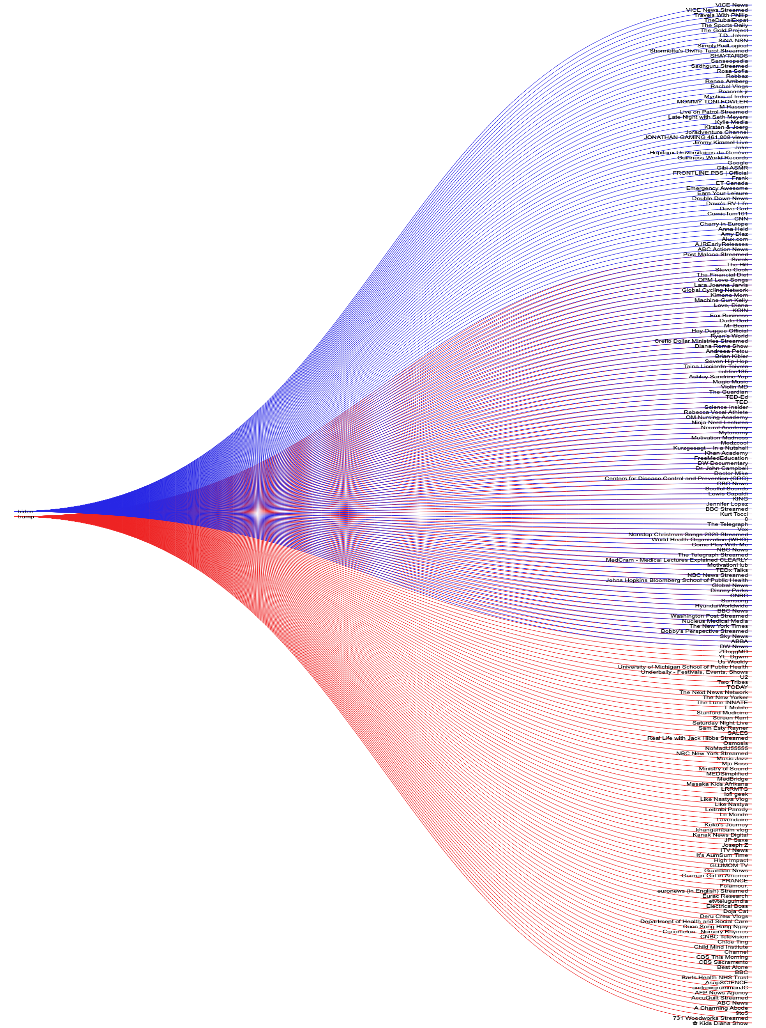

In the graph for the “american elections” query (figure 3), which represents all results retrieved, we can observe a slim overlap of videos offered to both groups by mainstream media ranging from Sky News, CNN, CBC News Streamed, the Economist etc. Outlets such as “Now This News”, “Democracy Now” and channels by individuals such as Evan Edinger are offered to Biden supporters only, while niche digital media outlets such as “Thinkr”, “Motivation Madness”, “RoTenDO” are offered as results only to Trump supporters.

Figure 3. Visualisation of data flows for the “american elections” query.

Finding 2: The search results for “american elections” in terms of the political orientation of the YouTube channels similarly indicate polarization, as conservative users are recommended more right-leaning channels, while the progressive users are recommended more left-leaning channels.

Figure 4: Top 20 search results of “american elections” across conservative (Trump pseudo) and progressive (Biden pseudo) user groups in terms of political orientations.

Figure 4 shows the clusters of recommended videos in the search results for “american elections” in terms of political orientation of the Youtube channel. It is worth noting that the cluster of videos in the center of the graph is mostly left-leaning and center channels, meaning that many left-leaning and center channels are recommended to all users. Moreover, we can clearly see that conservative users are recommended more right-leaning channels, while the progressive users are recommended more left-leaning channels. Therefore, the results indicate that polarization is happening in the search results for “american elections” on YouTube.

This is also evident in the charts representing the quantitative statistical analysis (figure 5)

Figure 5. Channel orientation of recommended videos per group of users for the “american elections” query.

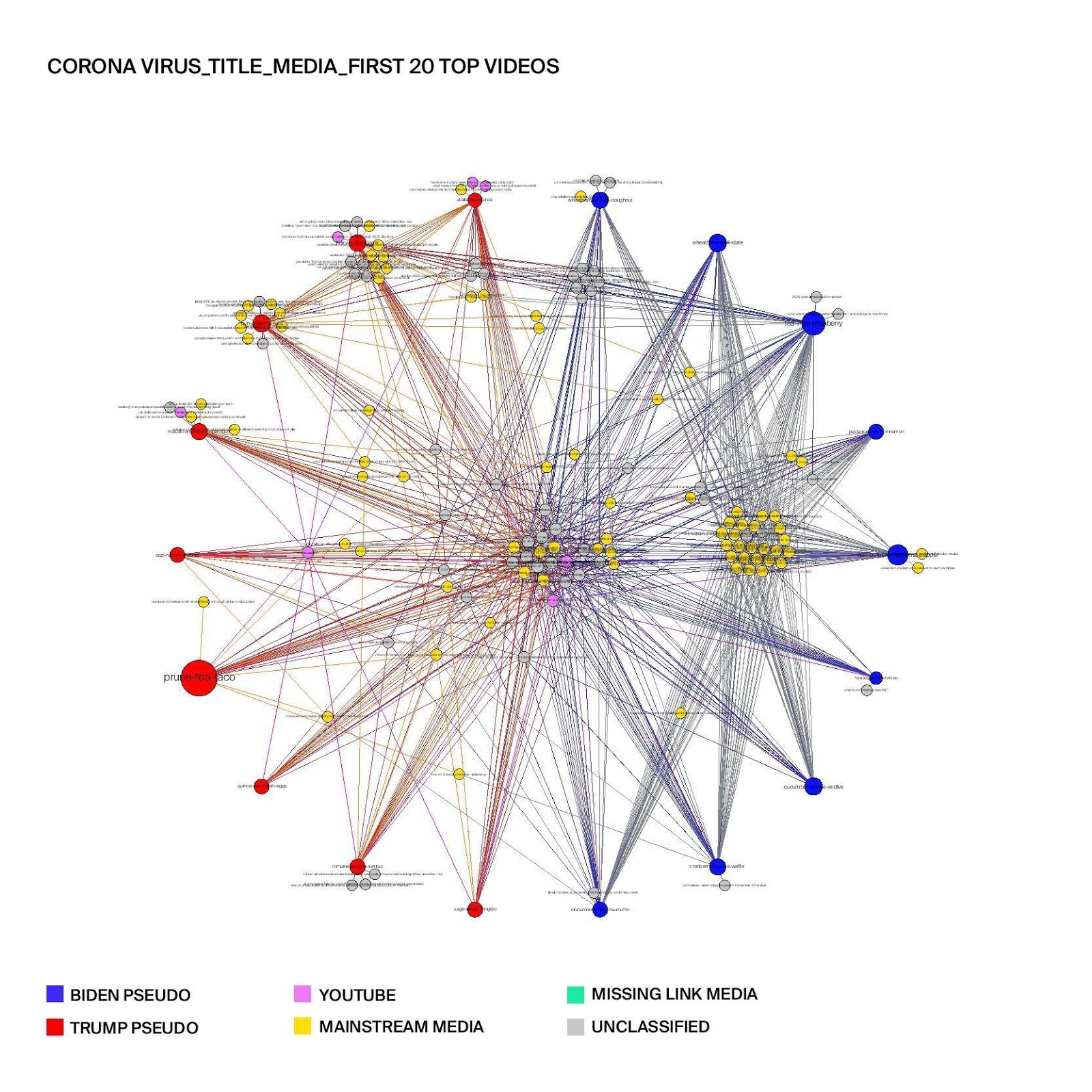

Finding 3: The search results for “Coronavirus” indicate less polarization in terms of the media type than the previous query for “American Elections”, as mostly mainstream media channels are recommended to both user groups.

Figure 6: Top 20 search results of “Coronavirus” across conservative (Trump pseudo) and progressive (Biden pseudo) user groups in terms of media types

Figure 6 illustrates clusters of recommended videos in the search results of “Coronavirus” coded in terms of media type. The graph shows that mainstream media channels dominate the results for both user groups, as both user groups are recommended almost only mainstream media and almost no youtube-native channels. The progressive user group share a number of same recommendations to mainstream videos among them - the concentrated cluster on the right of the figure - while the conservative user groups are provided with more fragmented search results beyond the ones recommended to all the users from the center cluster, indicating more personalization for this specific group. Based on these results, it can be assumed that YouTube has intentionally made sure that mostly verified information from mainstream channels are recommended to users searching for information on the coronavirus.

Figure 7. Visualization of data flows for the “coronavirus” query.

In the graph visualizing all results following the “coronavirus” query (figure 7) the channel overlap seems to be much larger in comparison to “american elections”, ranging from domain-specific channels such as the John Hopkins Institute for Public Health to news outlets ranging from VOX News to BBC News and Deutsche Welle. At the same time, Biden supporters are offered content by YouTube natives such as Evan Endiger, as well as conventional, mainstream outlets such as “The Economist”. Trump supporters are offered content by outlets such as the “Child Mind Institute”, “News Now from FOX” and “The Sun”.

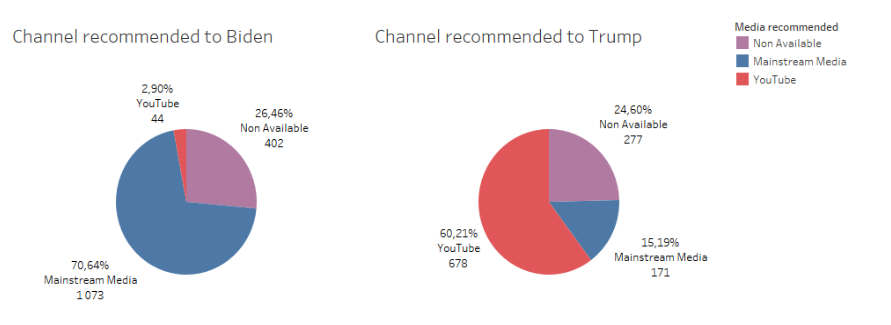

A quantitative statistical analysis of the data sets for the “Coronavirus” query (figure 8), replicates the tendency observed in the previous query “american elections”, showing that personalisation in content retrieval occurs through niche media outlets or native YouTube channels for the majority of users affiliated to Trump and mainstream media outlets for users affiliated to Biden.

Figure 8. Statistical Analysis. Proportion of media type per category of users for the “Coronavirus” query.

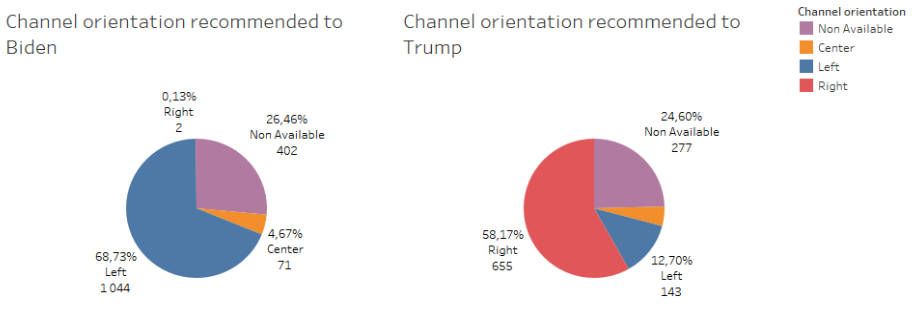

Finding 4: The search results for “Coronavirus” also indicate less polarization in terms of political orientation of the YouTube channels, as both user groups are recommended mostly left-leaning channels

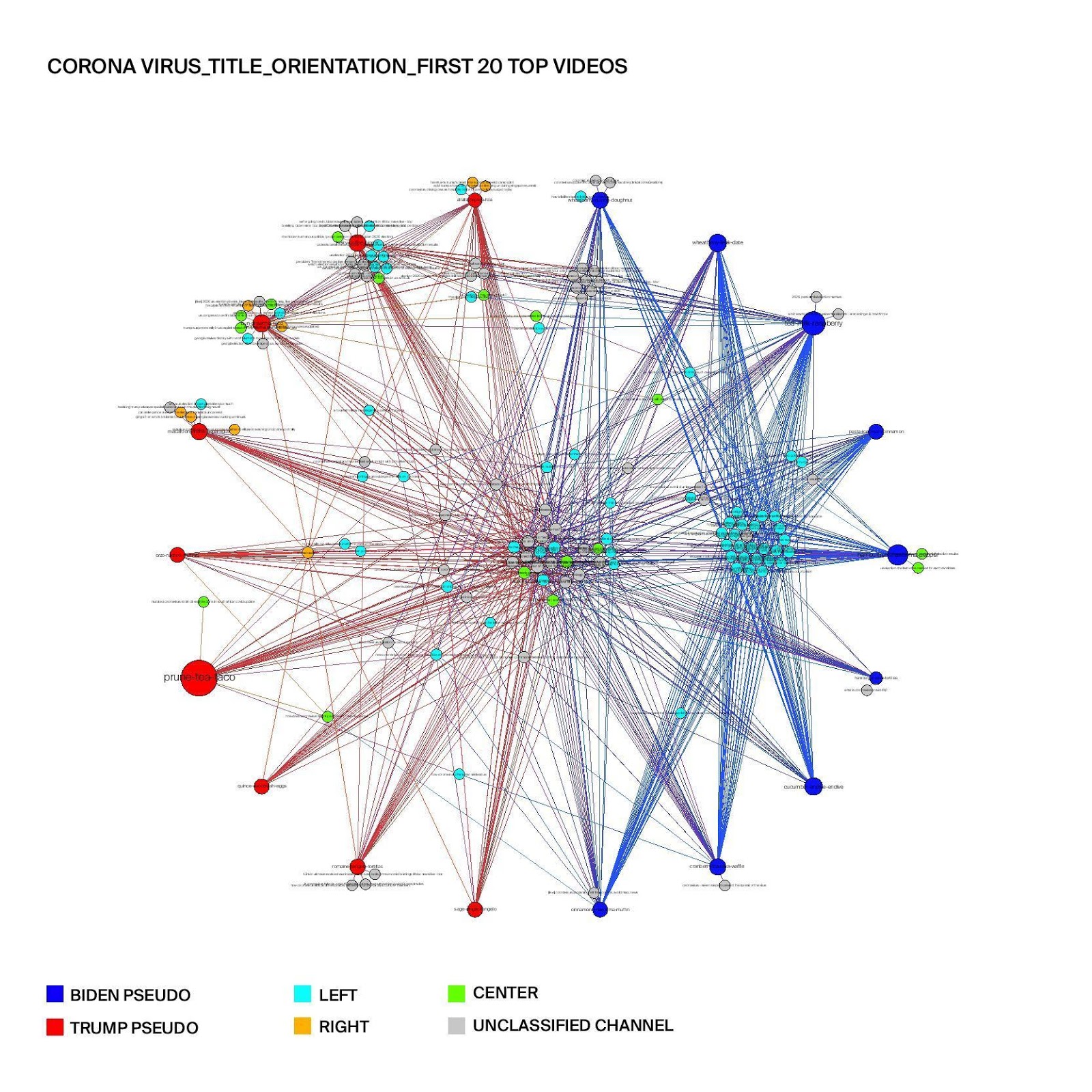

Figure 9: Top 20 search results of “Coronavirus” across conservative (Trump pseudo) and progressive (Biden pseudo) user groups in terms of political orientations.

When looking at the search results of “Coronavirus" in terms of the political orientation of the YouTube channels recommended, a lopsided recommendation emerges of left-leaning media content to both the conservative and progressive user groups. No right-leaning channels are recommended to the progressive user groups and only a few conservative users get personalized recommendations from the right-leaning channels. Thus, the results also indicate that conservative users get recommended videos with more diverse political orientations than the progressive users, when we focus on each user individually.

Nevertheless, the quantitative statistical analysis of all results following the “coronavirus” query (figure 10), indicate that personalization of results which was observed in the previous query “american elections”, is also replicated here. Republican supporters are offered predominantly right leaning channels, while Democrats are offered mainly left leaning outlets.

Figure 10, Channel orientation of recommended videos per group of users for the “coronavirus” query.

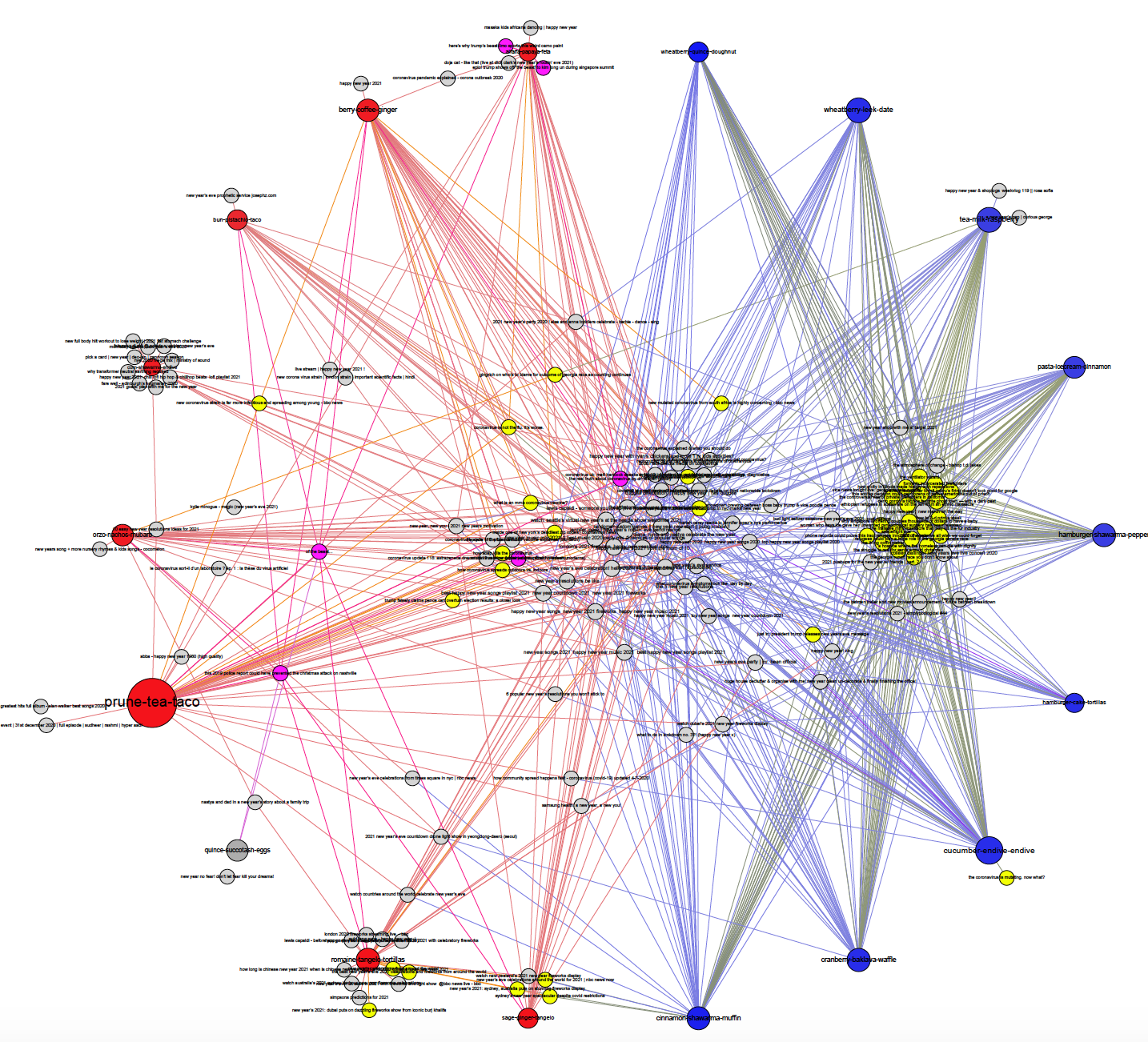

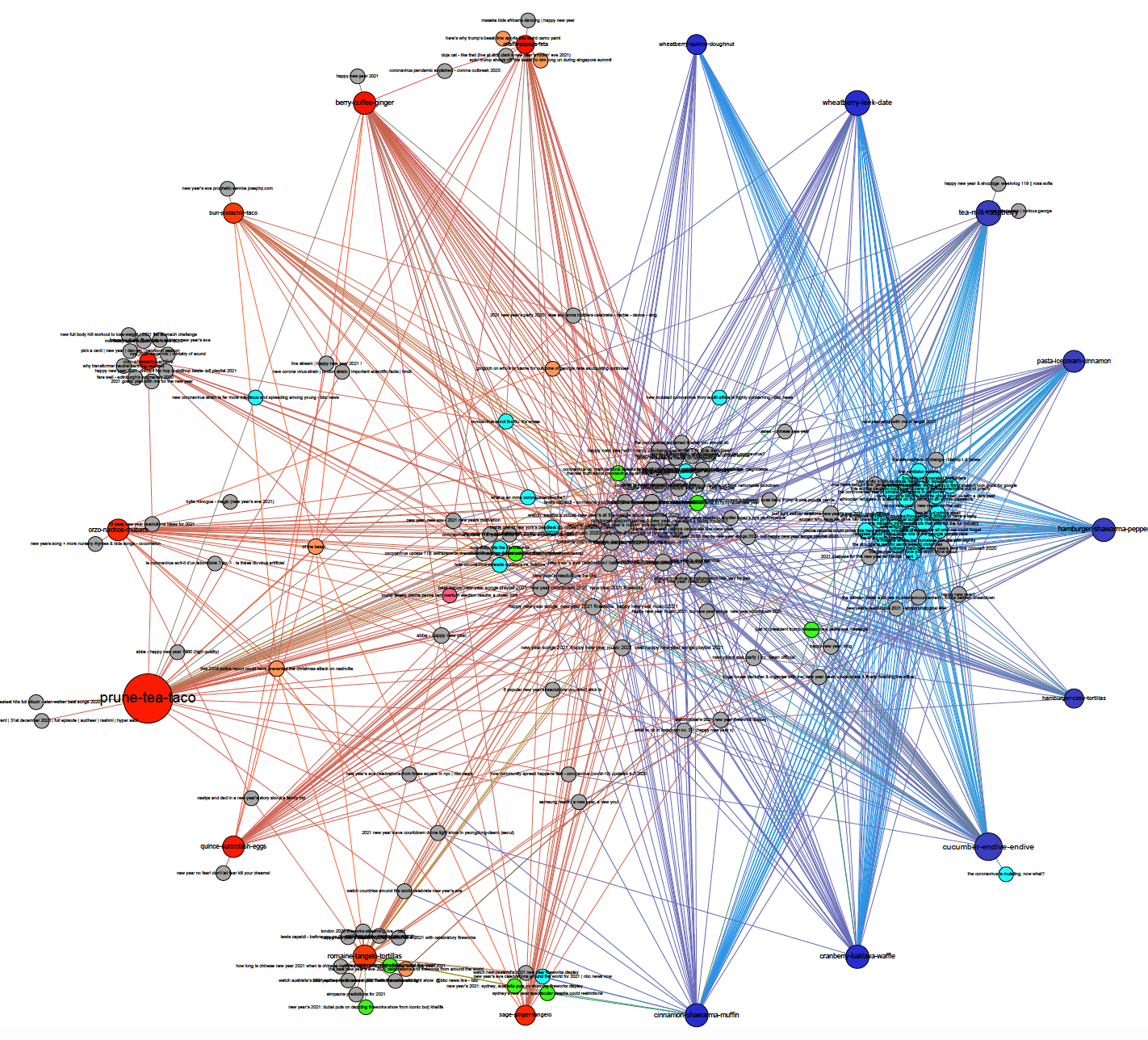

Finding 5: the results indicate that previous searches influence new searches, proving the so-called “carry-over effect”, as a number of recommended videos were related to the previous queries.

In the “Coronavirus” search results, there are quite a lot of personalized results for individual users related to the American election. These results indicate that the previous search for “american election” has influenced the next search, indicating a “carry-over effect” (Hannák et al, 2017). The same carry-over effect is evident in the search results for the control query “new year” performed last. Here, coronavirus-related suggestions appear for both user groups. The results are illustrated in the graphs below and indicate that neutral queries will get a lot of channels recommended that are not categorized in terms of media type and political orientation, as they are not news channels.

Figure 11: Top 20 search results of “new year” in terms of media type (left) and political orientation (right)

Finding 6: There are instances of unique search results for particular users within groups:

a) Unique search results of videos created in a non-English language or linked to geo-location data indicate personalisation processes beyond the variables we determined for the research.

b) Individual users are offered unique results in videos ranking beyond the 12th position. This may indicate polarisation and / or radicalisation processes where the content expresses extreme political views.

Finding 6a: Channels such as La NACION (n=1 user), 9 News Australia (n=1 user), India Today (n=2 users), the AFP News Agency (n=3 users) and The Sun (n=2 users) appear for the American Elections (figure 1). Similarly, ITV News (n=1 user), DW Deutsch (n=1 user), FRANCE (n=1 user) and 11 Alive Streamed Georgia (n=1 user), appear as unique results for the Coronavirus query (figure, 2). This could be a potential indication that personalisation processes are in progress which relate to variables linked to geo-location data and videos created in a non-English language. The YouTube ranking algorithm is reportedly drawing on geo-location data, among other variables, in order to infer the possibility of users to engage with similar content in the future (Covington et al, 2016).

Figure 12. Visualisation of data flows for the “New Year” query

Finding 6b: In the “New Year” query (figure 12) channel overlaps for both groups include traditional media outlets, such as the Washington Post Streamed, The Telegraph streamed, and Global News (Canada). However, if we look into the data flows after the 12th result, we have instances of the same channel offering different videos to individual users. The NBC News Channel appears as a result only to four users, two from each group. Interestingly, within the groups individual users are offered different videos.

For the “american elections” (figure 3) and “coronavirus” (figure 7) queries, there are also unique results for individual users, albeit expressing strong political views. This is observed only for Trump supporters. Particular individuals within the group (n=1 user) were offered unique video results, such as “Nobody Saw This Coming! Michelle Obama Came Out Today & Revealed Who She Really Is”, “Michelle Obama PRAISES BLM But There’s Just ONE Problem” and “What is constitutional militia”, all from “The Next News Network’’ which was used to create a particular echo chamber. The strong political views which these videos express in combination with the fact that they appear as unique results indicate that there is the possibility of a process of polarisation or even radicalization being in place.

2. Natural Language Processing Analysis

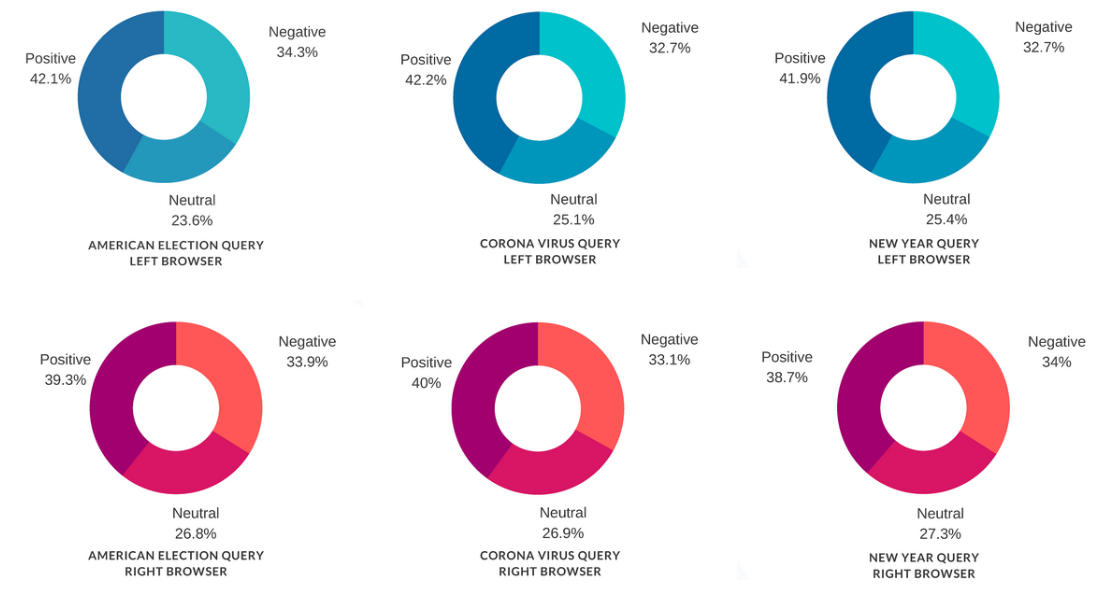

The sentiment analysis only revealed a proximity in the language on comments from both personalized selections. Negative and positive comments consistently outnumber neutral ones, but their distribution is almost equal across all queries and both personalized selections of videos. This offers no clue as to polarization.

Figure 13 : sentiment is the same for ‘conservative’ and ‘progressive’ personalized selections, and equally distributed for all queries

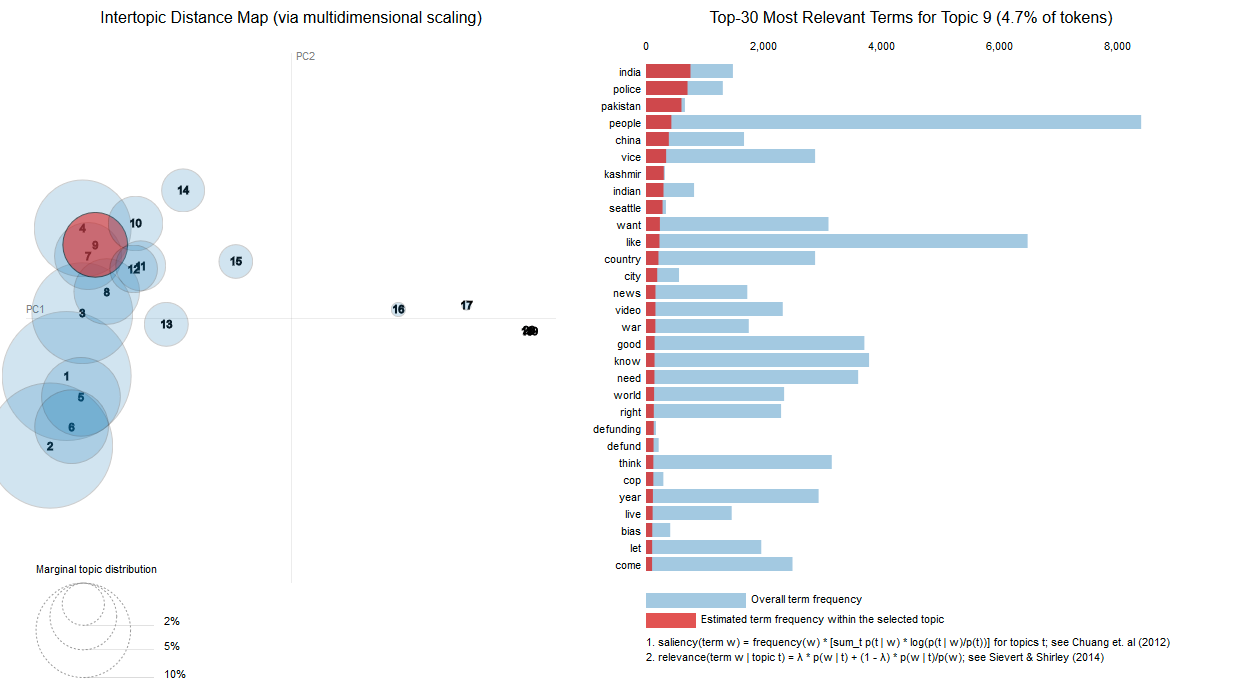

Finding 7: the personalization of search results leads to topics of discussion closely related to the previous activity of the user, regardless of the search itself. This indicates polarization in the case of a ‘conservative’ or ‘progressive’ user through the amplification of political views.

Figure 14 : Topics in the comments for the “American election” query results, as presented to the Conservative (14a) and Progressive (14b) user group.On the left hand side, the size of the bubbles reflect the importance of each topic. Their position is defined by the content (intertwined bubbles are topics closely related to one another). On the right, the details of a highlighted topic. Interactive version can be found here.

Figure 14 illustrates the main topics within the comments of the “American Election” videos. The graph shows significant differences in weight distribution and diversity of these topics, between progressive and conservative sides. Videos recommended to the progressive user group (figure 14a) present a larger number of different relevant topics (20 vs 14), and more variety within those topics. The main debate is about the election (bubbles 1 and 2) and displays an international world view with a number of country names being relevant to the topic. Smaller topics include the nobel peace prize (bubble n°13), space technology and a number of smaller international issues clustered around bubble n°9.

The selection for the conservative browsers, on the other hand, leads to a more polarized discussion, in the sense that there are less significant topics, and the top subjects are closer intertwined (similar concepts). Interestingly, the conservative selection seems to lead to more discussion of the Democrat candidate Joe Biden, whereas Donald Trump is mentioned more often in progressive videos. Still, as one would expect, within the theme of Elections, opposite profiles debate the same subjects. Our methodology provides little ability to gauge their opinions on those subjects, because the topics do not usually include adjectives. There is a difference in world view, which seems to mirror previous activity, but insufficient to call it polarization.

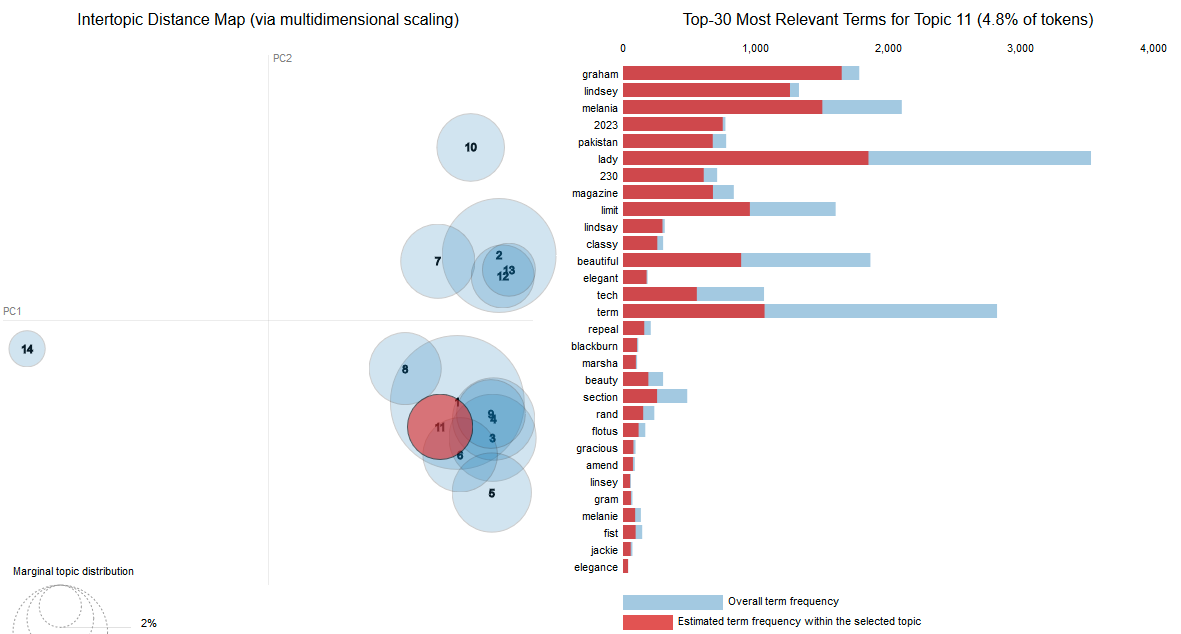

However, we find that political comments are even more prevalent and partisan within the “Coronavirus” videos, and even those of the supposedly neutral “New Year” query, as illustrated in figure 15.

Figure 15: Topics in the comments for the “New Year” query results, as offered to the progressive (15a) and conservative user group (15b). On the right-hand side we see the content of highlighted topics, related to the presidential candidates. Interactive version can be found here.

On figure 15b, signs of polarization first show through the content of the main topics. After the pandemic (bubble n°1) the most discussed subjects in the “New Year” conservative selection are the Trump presidency (bubble n°2), other political issues (n°3), and the democrats (n°4) - far outshining well-wishes for the new year (bubble n°7). Various democrat personalities are discussed, with the words “senile” and “dementia” being associated to Joe Biden.

The “progressive” selection of videos (figure 15a) shows a large cluster of political topics centered around Joe Biden (bubble 2) that we find to correspond to the profile of this user group. Commentators talk as much about the theme of the video as they do political topics. This is also the case for Coronavirus query. When they are brought up, they include social policies, international issues are discussed on a per-country basis, and discussion of the election is skewed in favor of Joe Biden with words like “win” and “vote” being more relevant within that topic (some suggested videos pre-date the election). Several topics are related to either appreciation or critique of media, and we find one related to police brutality and riots.

Across all queries, it is extremely rare that a topic be brought up on both sides in a similar fashion. The few topics that are common to both selections are still being discussed in a very different way, amplifying the world view from the user’s browsing history. Moreover, signs of polarization show even when taking into account videos that were offered to both user groups. In other words, YouTube personalized selection outweighs the content the site recommends to all users, in terms of the polarization of comments.

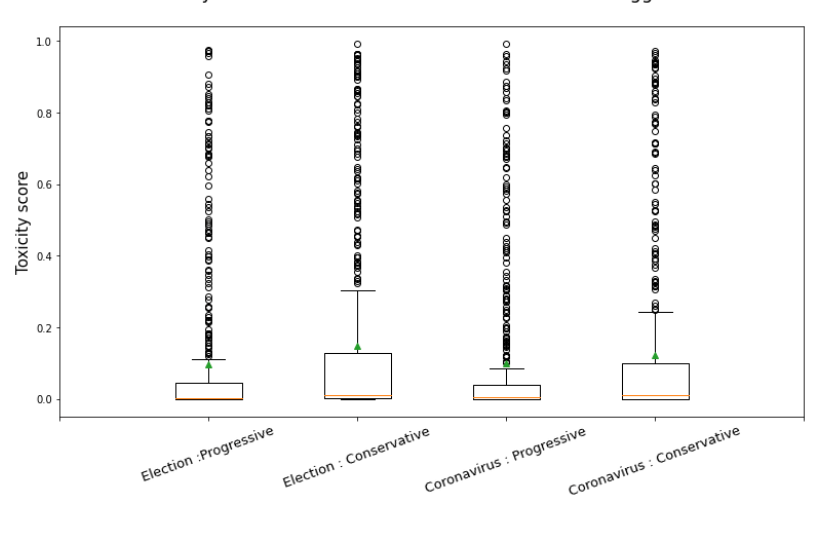

Finding 8: query results that were personalized for users having previously searched for, and consumed ‘‘conservative” media, contain a higher degree of toxicity within the comment section.

Figure 16 : Toxicity indices of the “Election” and “Coronavirus” query for both personalized selections

Fig. 16 shows that half of the comments are considered toxic across queries and personalized selections. For that half, comments in the videos suggested for the “conservative” browsers are considered toxic to a higher degree.

25 % of the comments of the videos suggested for those browsers have a toxicity score between 0.1 and 0.3. This surge in the number of toxic comments, and the degree of their toxicity, is not very high but remarkably consistent. It can be reproduced for smaller-size samples across all queries. Toxicity plays a role in polarization as defined by Gallacher & Heerdink (2019) and the YouTube personalization seems to lead the viewer to read, and participate in more toxic discussions, at least in the case of a “conservative” subject. It would be informative to perform this test on the “most relevant” comments as defined by YouTube, instead of random samples, to focus on what the viewer is immediately subjected to.

Discussion

This study found that the search results on YouTube differed across the conservative and progressive user groups in terms of the media type. The search results indicate that progressive users get recommended mostly mainstream media channels, while conservative users get recommended mostly YouTube native channels. The suggested videos’ political orientation also differs across groups, progressive users are recommended more left-leaning channels, while conservative users are recommended more right-leaning channels. Moreover, it is also worth noticing that more politically charged queries get more polarized results. We could also identify a few interesting differences in the topics and in the degree of toxicity emerging from the comments (not in sentiment), that can base a study on users’ polarization. However, more thorough sampling and analysis is needed.

However, the results so far are insufficient to prove the existence of filter bubbles on YouTube. All users are recommended a number of the same video suggestions, and personalized results appear to be mostly placed further down in the search results. Moreover, many personalized results stem from the same channels that the users previously watched in the personalization process.

Conclusion

The recent US Capitol Hill riot and subsequent “deplatforming” of President Donald J. Trump by YouTube and other social platforms underscored the US’s post-election social media environment’s increasingly polarized nature. Several weeks earlier, YouTube announced plans to make sure that the platform was not abused to incite real-world harm or broadly spread harmful misinformation. Therefore, this research’s significance is not only indicating the existence of filter bubbles but also highlighting the risk of personalized algorithms contributing to a polarized real-world and underscoring the importance of algorithmic mediation in the pursuit of democracy.

From another aspect, this research guides us on a direct path to further methodological improvements:

-

We found that the more users scroll to include search results, the more the results are influenced by the videos watched, meaning that scrolling through will provide more data.

-

We found that when users perform queries in sequence, the previous queries interfere with the later ones. Query interaction should thus be taken into account when comparing queries.

-

We found that the more videos a user watches, the clearer the results.

Thus, a more powerful echo chamber can be simulated by using automatic users to watch a more significant amount of videos. We implemented two different scripts to do so (1, 2), and with these, further research is needed taking scrolling activity and query interaction into consideration. Another interesting improvement of the methodology we tested could be using the Automated Integrative Complexity and the subtitles of the videos suggested by the algorithm, not just to the comments they received.

References

Adomavicius, G. and Tuzhilin, A. (2005). “Personalization Technologies: A Process-Oriented Perspective”. In Communications of the ACM, 48 (10), pp. 83-90.

Bastian, M., Heymann, S. and Jacomy, M. (2009). “Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks”. In Proceedings of the Third International ICWSM Conference, pp. 361-362.

Bozdag, E. (2013). “Bias In Algorithmic Filtering And Personalization”. In Ethics and information technology, 15 (3), pp. 209-227.

Bruns, Axel (2019): Are Filter Bubbles Real? Cambridge, UK/Medford, MA: Polity Press.

Bryant, L.V. (2020). “The YouTube Algorithm and the Alt-Right Filter Bubble”. In Open Information Science, 4 (1), pp. 85-90.

Buckland, M. and Grey, F. (1994). “The Relationship Between Precision and Recall”. Journal of The American Society for Information Science, 45 (1), pp. 12-19.

Castree, N., Rogers, A. and Kitchin, R. (2013). “A Dictionary of Human Geography.” Oxford University Press.

Conway, L. G., III, Conway, K. R., Gornick, L. J., & Houck, S. C. (2014). Automated integrative complexity. Political Psychology, 35, 603-624. DOI:10.1111/pops.12021

Covington, P., Adams, J. and Sargin, E. (2016). “Deep Neural Networks For YouTube Recommendations”. I RecSys ‘16 Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, pp. 191-198. https://doi.org/10.1145/2959100.2959190

Hannák, A., Sapiezynski, P., Molavi Kakhki, A., Krishnamurthy, B., Lazer, D., Mislove, A. and Wilson, C. (2013). “Measuring Personalization of Web Search”. In WWW'13: Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on World Wide Web, pp. 527-538. https://doi.org/10.1145/2488388.2488435.

Houck, S. C., Conway, L. G., III, & Gornick, L. J. (2014).”Automated integrative complexity: Current challenges and future directions.” Political Psychology, 35, 647-659. DOI:10.1111/pops.12209

Gallacher, J. D., Heerdink, M. W., & Hewstone, M. (2021). “Online Engagement Between Opposing Political Protest Groups via Social Media is Linked to Physical Violence of Offline Encounters.” Social Media andSociety, 7(1).

Kaiser, J. and Rauchfleisch, A. (2020). “Birds of a Feather Get Recommended Together: Algorithmic Homophily in YouTube ’s Channel Recommendations in the United States and Germany.” In Social Media and Society, 6 (4). https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2056305120969914

Nikas, J. (2018). “How YouTube Drives People to the Internet’s Darkest Corners.” The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-youtube-drives-viewers-to-the-internets-darkest-corners-1518020478

Marwick, A. and Lewis, R. (2017). “Media Manipulation And Disinformation Online.” New York: Data & Society Research Institute.

O’Callaghan, D., Greene, D., Conway, M. and Carthy, J. (2013). “The Extreme Right Filter Bubble”. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1308.6149.

Pariser, E. (2011). “The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding From You.” London: Viking.

Pew Research Center (2020). “Many Americans Get News on YouTube, Where News Organizations and Independent Producers Thrive Side by Side”. https://www.journalism.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2020/09/Many-Americans-Get-News-on-YouTube-Where-News-Organizations-and-Independent-Producers-Thrive-Side-by-Side.pdf

Robertson, R., Lazer, D. and Wilson, C. (2018). “Auditing The Personalization And Composition Of Politically-Related Search Engine Results Pages”. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference, pp. 955-965.

Sanna, L., Romano, S., Corona, G. and Agosti, C. (forthcoming). “YTTREX: Crowdsourced Analysis of YouTUbe ’s Recommender System During COVID-19 Pandemic”.

Zimmer, F., Scheibe, K. and Stock, W.G. (2019). “Fake News in Social Media: Bad Algorithms or Biased Users?” In Journal of Information Science Theory and Practice, 7 (2), pp. 40-53.

Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. J., Trilling, D., Möller, J., Bodó, B., Vreese, C. H. de and Helberger, N. (2016). “Should We Worry About Filter Bubbles?” Internet Policy Review, 5 (1). https://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/should-we-worry-about-filter-bubbles

Appendix

Please refer to original document.